AN EERIE REMINDER

Current situation reminds locals of 1980 eruption

May 14, 2020

Ledger File Photo

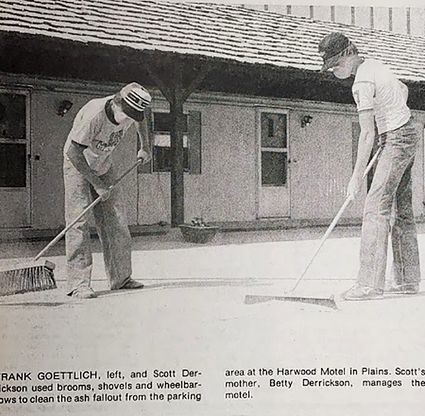

SWEEPING ASH from the parking lot of the former Harwood Motel in Plains were Frank Goettlich (left) and Scott Derrickson.

It was almost 40 years ago that the Northwest was in the midst of a different kind of crisis. On May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens erupted in Skamania County, Washington, resulting in the deadliest and most economically destructive volcanic event in U.S. history. The eruption killed 57 people and decimated buildings and vegetation within a 230 square mile radius.

According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the glowing cloud of super-heated gas and rock debris that shot out of the volcano during the eruption was created because of the abrupt release of pressure over the magma chamber. The gas and debris were blown out of the mountain face moving at nearly supersonic speed. Everything within eight miles of the blast was wiped out completely.

At 9:32 a.m. mountain daylight time on that Sunday in 1980, plumes of ash took over the sky, spiraling upward to 16 miles above sea level. USGS states, "about 540 million tons of ash from Mount St. Helens fell over an area of more than 22,000 square miles." Because of the strong, high-altitude winds, the plume of ash moved east at 60 miles per hour, reaching eastern Montana by noon.

While it only took a few hours for the ash to arrive in Montana, by the next day the state was cloaked in a blanket of ash. From The Sanders County Ledger May 22, 1980 edition, "the ashen cloud moved into Sanders County late Sunday afternoon and by dark, the ash fallout resembled a soft winter snow storm as the flakes floated to the ground."

Montana Gov. Thomas Judge declared a state of emergency and ordered all travel, except extreme emergency, to be halted. All non-essential businesses closed and residents were ordered to stay inside.

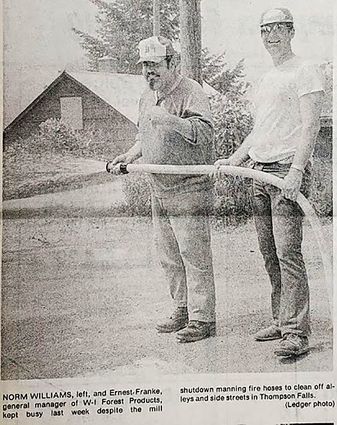

Ernie Franke, a Thompson Falls resident since 1940, was the general manager at one of the local sawmills at the time. Franke, who managed 180 employees, was deemed "essential" during the crisis. "It was on a Sunday, I was working in the garden," Franke said as he recalled the events that happened on that eerie day in May.

Franke, who was in the thick of it all, was utilized during this time. His water trucks from the sawmill were put to good use in helping clean up the fallen ash around town. "For a week, I sent my water trucks out to water down the streets. I couldn't believe it came this far, that fast. We had a quarter to half an inch here. I never thought I would see green grass again," Franke said. "I wish I had a penny for every time I washed down those streets," he continued.

He described the experience as "unreal." Franke said the only way to truly understand an experience like that was to live through it.

"The gray ghost which enveloped western Montana affected everyone. Schools, businesses, government offices and lumber mills all closed," The Ledger reported. The only school to open that Monday in Sanders County was Noxon. According to Sheriff Harvey Schultz, it closed shortly after it opened and all students were sent home.

While the courthouse was the exception and opened on Monday for business, W-I Forest Products, Flodin Lumber Company and other mills were closed. The newspaper didn't arrive in Thompson Falls on Monday morning, and all mail services were shut down.

Jeff Wheeler, a retired Thompson Falls High School teacher, was selling real estate at the time. While he was showing his client a house in Plains, he remembers mentioning how it looked like a storm was coming in.

At the time, Wheeler was unaware of the eruption. "I had no idea it happened. In the aftermath of it all, I was stuck in Plains," Wheeler said. "It felt very much like what it feels like right now," he said, referring to the stay-at-home order that was issued because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Wheeler, who recalls being stuck in the house for a solid three days, says it was a lot harder back then to stay put. "I was younger back then," he chuckled. "There was nowhere to go. All the stores and bars were closed, we couldn't leave the house."

After about three days, the Plains Fire Department started to wash down the streets. Wheeler said the local outdoor tennis court was washed down as well. "So that's what we did to get out, we went and played tennis."

In the days following the eruption, Sanders County residents did what they could to clean up from the aftermath of the eruption. Gambles store reported they quickly sold out of auto air filters and face masks.

As ash covered the ground, towns around Sanders County came to a stop. The Ledger reported that the fallout spread as far north and east as Lethbridge, Alberta, and as far south as the Texas panhandle and into North Dakota. Studies showed that Great Falls and Helena received more ash than Bozeman and Billings. Ash from the eruption was reported as far east as Minnesota and Oklahoma.

Tests done by Don Merryman at Lawyer Nursery in 1980 computed the ash falling in Sanders County to be about 3,000 to 3,500 pounds per acre. While that may seem like a lot, it was shown the ash contained a small amount of acid.

County Agent Barry Bowels told The Ledger the week after the eruption that "soil tests on the ash falling from the Mount St. Helens volcano conducted Monday by the Montana State University (MSU) at Bozeman shows the acid is almost neutral and its acidity is less than that found in vinegar." Tests done by MSU also revealed the ash contained a slight amount of sulphur, "about two parts per million," which in the long run reportedly helped the soil fertility in Montana.

Cleaning of the town started the following week. The city's water trucks and Thompson Falls firemen used their trucks' main water pumps to wash down sidewalks and other areas along Main Street and around town. City Superintendent Larson reported to The Ledger "all paved streets and even some graveled alleys in town were washed down to remove fine ash. Some streets got five or six washings." The city's estimated expenditures were $10,000 and Plains estimated $8,500.

Ledger File Photo

NORM WILLIAMS (left) and Ernest Franke use a fire hose to clean off a Thompson Falls Street.

The ash and dust lingered in the air for nearly a week in Sanders County. For the residents who lived through the experience, the memories of the ash falling from the sky like a winter snowstorm are as vivid today as they were 40 years ago.

Reader Comments(0)